South Africa’s First Coinage Issues

- wcnumsoc

- Aug 22, 2023

- 7 min read

Pierre H Nortje (August 2023)

This short paper takes a look at coinage that was issued before 1874 for exclusive usage in South Africa. These issues therefore predate our first coin that carries the name of South Africa, which is the Burgerspond.

Source: Numista (Heritage Auctions)

The first coins to circulate in South Africa were those introduced by the Dutch at the Cape in

1652. However, these coins were issued by various countries and circulated internationally, especially among sea-faring nations. Therefore, they are excluded from the scope of this paper.

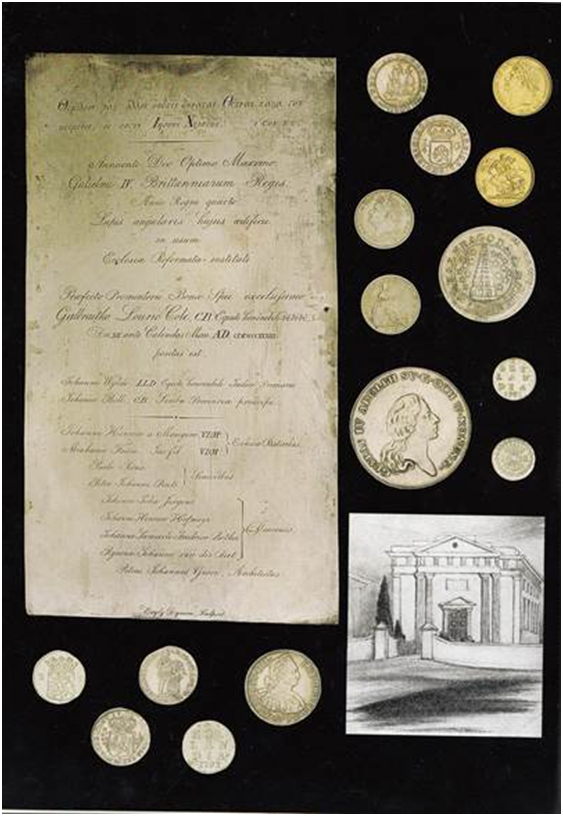

Fifty-six years ago, in 1967, die Nuwe Kerk, a church building of the Dutch Reformed Church in Cape Town, was demolished. An engraved silver plaque on the foundation stone proclaimed in Latin that it has been laid by the British Governor at the Cape of Good Hope, Sir Galbraith Lowry Cole on 20 April 1833 during the reign of King William IV. When the foundation stone was removed during the demolition, a collection of 20 coins was found with other contemporary articles such as a newspaper. The late Dr. Frank Mitchell who examined this hoard, speculated “… that all the coins so carefully placed under the stone were pieces which were familiar, and presumably in circulation, in Cape Town at the time.”

The hoard included 9 pieces from Great Britain, 8 from the Netherlands and 3 from other countries. Included was a ¼ Scheepjesgulden. This picture above right was published in 1986 in Numismatic Essays – a publication by members of the South African Numismatic Society. It shows some of the coins found in the hoard with the ¼ Scheepjesgulden of 1802 at the top to the left of the gold Sovereign.

The Scheepjesgulden dated 1802 were the first coins minted specifically for use in South Africa. With the Treaty of Amiens on 27 March 1802, the Cape was returned by Great Britain to the Batavian Republic who sent Commissioner-General Jacob Abraham de Mist to the Cape to oversee the installment of the new Governor, Jan Willem Jansens.

De Mist (left) and a model of the Cape at around the time he arrived. Source: Wikipedia

At De Mist’s request, 100,000 Guldens were minted for the Cape in denominations of 1, ½, ¼, 1/8, and 1/16 in silver, as well as copper doits and half-doits. However, the coins were not named for the Cape, but instead were inscribed with the words 'INDIAE BATAVORUM,' as the Cape was considered one of the Eastern possessions of the Batavian Republic. These coins were struck by Hessel Slijper, the Mint Master of the Dutch Mint in Enkhuizen.

The 1/8th Scheepjesgulden. Source: Schulman Auctions

When De Mist arrived at the Cape, the British occupation troops had not yet left and most likely made him order the entire shipment of coins to be forwarded to the much safer Batavia in Java, Indonesia. A few months later, another shipment of guilders arrived at the Cape but was kept in safekeeping and, for some reason, was not put into circulation. The coins were only circulated three years later, ironically not by the Dutch, but by the new British occupiers after they retook the Cape in 1806.

It is important to note that this second consignment of Scheepjesgulden consisted only of the silver ½, ¼, 1/8, and 1/16 issues. Therefore, it is thought that the 1 Gulden and the copper doits and half-doits probably never circulated at the Cape.

For reference, the Doit, the higher of the two copper denominations, is depicted on the left, and the 1/16 Gulden, the lowest of the five silver denominations, is shown on the right. Although both are marked '1/16,' causing potential confusion, a closer look reveals the figure '5' positioned to the left of the lion on the Doit. This signifies that 5 of these Doits are equivalent to a 1/16th Gulden.

A decade later, in 1816, the so-called Griqua coinage was struck in England upon the order of the London Missionary Society for use as a circulating medium at their mission station in Griquatown. The LMS referred to these coins as 'tokens,' and they were issued in four denominations: ¼ and ½ in copper, and 5 and 10 in silver. Neither their denominations (e.g. penny) nor the date of their manufacturing is depicted on them. It is believed that the consignment arrived in South Africa the following year (1817) and was subsequently forwarded to Griquatown. The coinage saw only limited usage, as the missionaries struggled to ascertain the value of the silver pieces. Those that were initially circulated were undervalued, resulting in a detriment to the society, who inadvertently short-changed themselves.

Source: Author’s library

It is recorded that £200 were initially approved for striking the silver pieces, but the cost and funding of the copper pieces is unknown. Recently, a few copper pieces were discovered by a metal detectorist at an old mission station of the London Missionary Society in Kuruman, located in the Northern Cape.

In 1834, the 40th report of the London Missionary Society reports on the contributions received at the South African mission stations. It states that £98-6-4 worth of Griqua coin(s) were sold in South Africa (probably to a local metal scrap dealer in Cape Town).

The report states that the total South African contribution received from the 7 mission stations was “received and expended” in South Africa”, so neither the coins nor the funds received from selling them were sent back to England.

This amount constitutes virtually half the amount initially approved for their manufacturing, at least for the silver pieces, so the question remains – what happened to the other half of the consignment sent to South Africa one and a half decades earlier – were they all circulated?

The third recorded coinage issued for usage in South Africa, to which the author found reference, was, according to R.B. Beck, also missionary tokens. As Beck notes, "Workmen and servants were usually paid in beads, though at Wesleyville in 1825, William Shaw was paying wages with a kind of tin token - about the size of a sixpence and stamped with a W, each token passes current, on the place and neighborhood, for five strings of beads, the daily wages of a man". The Wesleyville Missionary Station, founded by William Shaw in 1823 among the Gqunukhwebe, stands as the first Methodist Missionary Institution in Xhosaland.

Source: Wikimedia

These Wesleyville tokens are not documented in any of the well-known South African token reference books. To the best of the author's knowledge, none of them has ever been offered for sale, and if surviving specimens do exist, they must be exceedingly rare.

Four years later, in 1829, a communion token was issued in Cape Town by the Presbyterian Church. Communion tokens were also issued by the Free Church of South Africa in 1846, the Presbyterian Church of Port Elizabeth in 1862, and the Ebenezer Church in 1871. However, these tokens were not intended as a substitute for money, so they are not particularly relevant to this paper.

Source: MTB South Africa Tokens

After the Wesleyville tokens, issued in 1825, the first true monetary token we were able to find is the Durban Club Sixpence (6d) issued in 1860.

Source: Stacks Bowers Galleries

This leaves a period of 35 'dry years' in between. The reason for this gap is not known. However, one must take into account that in 1817, Sir Edward Littleton, a member for Staffordshire, introduced a Bill in the Parliament of Great Britain to prohibit the production of copper tokens and to make the circulation of such tokens illegal after January 1st, 1818. The Government successfully passed the Bill on July 27th, 1817. This law also extended to the colonies; for example, all copper tokens issued in Canada were considered illegal after that date. The author is unaware of when this bill was withdrawn, but it appears that during the 1860s, the issuance of tokens in South Africa became more widespread.

In 1861, at least four token issues are known to have been circulated. These include Blackwood & Couper of Durban (3d, 6d & 1/-), McArthur Muirhead & Co also of Durban (3d, 6d & 1/-), the Crown Billiard Club in Pietermaritzburg (6d), and Whyte & Co of Cape Town. The last mentioned has no monetary value indicated on it and was probably an advertising token. In 1867, Daniel & Hyman of Bloemfontein issued denominations of 6d, 1/-, 2/-, and 2/6-, while in 1872, Morris’s Hotel in Grahamstown issued a One Penny Token.

Source: Numisbids

Other tokens are also known to have been issued in South Africa up to at least the early 1870s. The exact years for some of these tokens are not known. Examples include Parks J. 3d, Cape Mounted Riflemen 3d Canteen Token, Gowie Brothers Advertising Token, James Macneill ½d & 1d, Marsh & Sons ½d, Royal Hotel (JE Wagner) 1d, and Wagner & Von Poellnitz overstamped 5/-

It's interesting to note that none of the South African tokens predating the Burgerspond in 1874 were struck for usage in the Transvaal, but rather in the British colonies of the Cape of Good Hope and Natal, with one instance even extending to the Orange Free State. On a lighter note, this could be the reason why the Transvaal (Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek) "took revenge" by issuing the first South African coinage range named after our country in 1892 - the well-known and widely collected Paul Kruger series. British soldiers even collected these coins during the Boer War; the accompanying image was published in "With the Flag to Pretoria" in 1900.

The Union of South Africa was established on May 31, 1910, through the unification of the Cape, Natal, Transvaal, and Orange River colonies. Thirteen years later, in 1923, the first coins were struck for the united South Africa.

Source: The Coin Cabinet

Postscript

In Volume 2 of 'De Nummis,' the Journal of the Transvaal Numismatic Society, published for the years 1956/1957, Dr. F. Machanik presented a highly insightful article titled 'The Iron Currency of Africa.' This article, available digitally in our WCNS library, explores the differentiation between the terms 'Currency' and 'Money' in its introduction.

Currency is exchange through a medium. This medium was in primitive society the use of such things as cowrie shells, beads, and lumps or bars of metal, etc. Money was the medium in the form of a token or coin, and had a more uniform and standard value.

While this paper did not cover these primitive forms of currencies, they hold significance in the broader context of our South African numismatic heritage. Readers are encouraged to read Dr. Machanik's article for further insight.

In our WCNS library, readers will also discover references to articles such as 'Old Copper Currency of the Northern Transvaal Tribes,' transcribed from the Transvaal Numismatic Society meeting of December 12, 1951. Additionally, 'Boesman Geld (Bushmen Money)' can be found in Bickel's Coin and Medal News from February 1967 (page 6). Regrettably, these articles are not currently digitized on our website.

Bibliography

Beck, R.B., Bibles and Beads: Missionaries as Traders in Southern Africa in the Early Nineteenth Century, The Journal of African History, London, 1989.

Carroll, Dr. M. & Jacobs, A. MTB South Africa Tokens, Hanoi Publishing House, 2021

Cribb, J. Cook, B. & Carradice, I., The Coin Atlas –The World of Coins from its Origins to the Present Day, MacDonald Illustrated, 1990.

Hern, B., Hern’s Handbook on Southern African Tokens, Ferndale, Johannesburg, 2009

Nortje, P.H., The Mystery of the Missionaries’ Money – The Griqua Coinage of the London Missionary Society, New Voices Publishing, 2023.

Vinkenborg, J., De Geuzenpenning en Penningkundige Nieuws, 9 de Jaargang, No 3, Juli 1959.

Comments